As evidenced by the strong growth in asset managers and owners subscribing to the Principles for Responsible Investment, a global initiative that aims to create a more sustainable global financial system, investors increasingly care not only about their financial performance, but also about the sustainability characteristics of their investments. Investors also increasingly work to align their investment portfolios with global agreements such as the Sustainable Development Goals and the Paris Agreement on climate change. In our recently published paper, which is forthcoming in the Journal of Impact and ESG Investing, we empirically examine whether unsustainable firms have been deprived of fresh capital by investors.

Motives for divestment

There are three different motives for divestment from unsustainable businesses. Some investors divest from such companies for normative reasons, while being indifferent to the effect in the real world. Other investors view their divestment choice as a signaling tool but acknowledge that it may not have any direct impact on the firm. The most ambitious objective is to use sustainable investing as a way to support sustainable companies and hurt unsustainable firms, thereby using (the threat of) divestment as an incentive to improve corporate behavior. It may sound obvious that divestment negatively affects the target firm, but this mechanism is not so clear-cut. The issue here is that divesting is merely a transfer of ownership from one investor to another, which has no direct impact on the firm. However, divestment may hurt firms indirectly, by lowering their stock price, which is another way of saying that it is increasing their cost of capital. As a result, new projects will have a lower net present value, making it less attractive for a firm to expand its business operations. Divestment on a sufficiently large scale may even come down to a boycott that effectively blocks a firm’s access to capital markets.

The impact of sustainable investing on primary stock and bond markets

The ultimate impact of sustainable investing on listed firms is best evaluated by studying the primary market, i.e. new stock and bond issuance. Most research focuses on the secondary market, where the ownership of listed stocks and bonds is exchanged between investors. The challenge with examining the secondary market is that the aggregate effects of sustainable investing add up to zero, because if one investor has a portfolio with a lower carbon footprint, then, by definition, another investor will have a portfolio with a higher carbon footprint. The effects that secondary market activity have on the firms in question may be better observable in the primary market, when firms want to raise fresh capital. If sustainable investing is effective at significantly increasing the cost of capital of unsustainable firms, or even blocking their access to capital markets entirely, then one would expect to see this reflected in capital flows in the primary market.

Data on issuance in the primary market and corporate sustainability measures

To assess which firms raise fresh capital, we classify a firm as an equity issuer if its number of shares outstanding increased by at least 10% over the year. Similarly, we classify a firm as a debt issuer if the book value of its debt increased by at least 10% over the year. Our sample covers the period from 2010 to 2019. We consider a sample consisting of about 2,500 large and liquid stocks listed in 23 major developed and 27 major emerging markets.

We use a broad range of metrics to capture the various styles of sustainable investing. First, for the ESG dimension, we use the ESG scores from a variety of leading ESG-data providers: S&P Global, RobecoSAM, Refinitiv, and Asset4. It is important to consider ESG scores from multiple providers since the correlation between the scores of different providers are known to be low. For the carbon footprint dimension, we consider the carbon intensity of firms, which can be used as a screen to align portfolios with climate change mitigation objectives. We use carbon intensity data from RobecoSAM and TruCost. Finally, for the SDG dimension, we use the SDG-scores from RobecoSAM.

Sustainability profiles of equity and bond issuers

We assess the sustainability profile of equity and bond issuing firms versus the markets by comparing their average scores on the various sustainability metrics. If unsustainable firms have difficulty in obtaining fresh financing, we would expect that to show up in the form of better average sustainability scores of issuers.

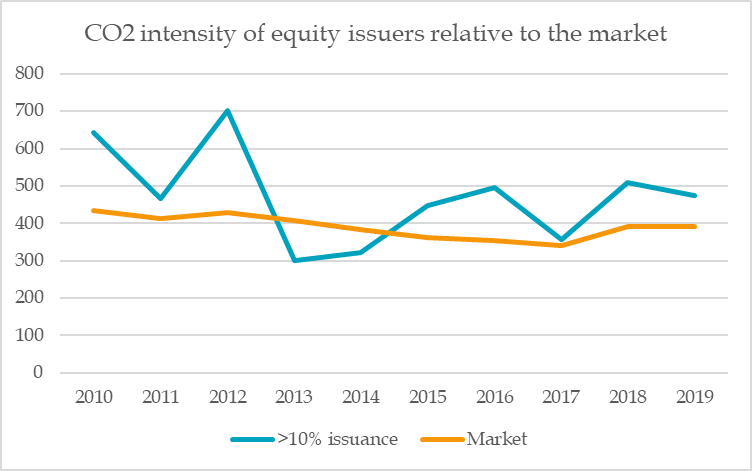

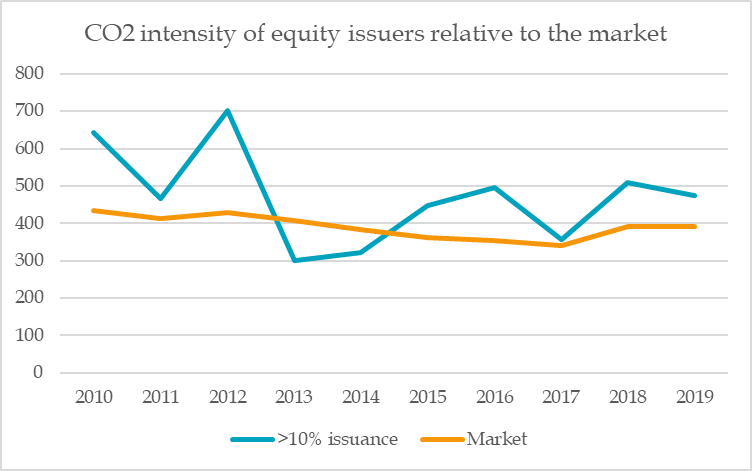

In the paper, we analyze nine sustainability measures in relation to equity and bond issuance. Here, we display only one such metric, the RobecoSAM CO2 intensity score, for illustration. The top figure depicts the average C02 intensity of equity issuers versus the market for each of the last ten calendar years, while the bottom left contains bond issuers instead. Only in two out of the ten years was the CO2 intensity of equity issuers (2013, 2014) and bond issuers (2014, 2016) lower than that of the average company. But in none of these cases was the difference statistically significant. This is the opposite of what we would expect if sustainable firms would attract more capital flows. We see similar patterns for the eight other sustainability metrics that we examine in the paper.

Implications

Our results suggest that sustainable investing has, so far, not been effective at depriving unsustainable firms from fresh capital. We acknowledge that our findings do not disprove the possibility that unsustainable firms would have been able to raise even more capital in the absence of sustainable investing. We also acknowledge that if sustainable investing continues to grow, it may become increasingly hard for unsustainable firms to obtain fresh funding in the capital market. However, it is an open question how much sustainable investing would be needed for that, and if such a scale is realistically attainable. In order to deprive unsustainable firms of fresh capital, sustainable investing probably needs to become “business as usual” in the investment community, rather than a niche adopted only by some.

David Blitz is the Chief Researcher at Robeco in the Netherlands

Laurens Swinkels is a Senior Researcher at Robeco in the Netherlands and an Assistant Professor at Erasmus School of Economics

Jan Anton van Zanten is SDG Strategist at Robeco in the Netherlands and a PhD candidate at Rotterdam School of Management