For a large number of European economies, real estate accounts for more than 70% of wealth, whereas financial assets usually account for below 20%. From a macroeconomic perspective, the large exposure to the real estate market represents both a vulnerability and a source of resilience: on the one hand, it exposes a large share of the population to a potentially illiquid asset; on the other hand, borrowers can accumulate wealth and provide savings to the financial system. In periods of high sovereign debt rollover needs, governments can adopt formal and informal financial controls on domestic banks, inducing a high level of sovereign exposure in financial institutions. Understanding how these factors are connected is important for the study of the liquidity and stability of the financial sector.

In a recent working paper, we examine the effect of government pressure on banks to allocate sovereign securities (moral suasion) on household lending under different scenarios regarding real estate wealth concentration, with and without banks’ balance sheet regulation. We shed lights on a new mechanism on the role of real estate wealth concentration for banks deciding how to allocate their lending to the private sector or to the government.

Households’ exposure to real estate and government debt allocation

Real estate wealth is both a consumption good (providing housing services) and an investment good: a considerable population (about 20%) owns real estate other than their main residence. Countries in the sample Household Finance and Consumption Survey show high exposure to real estate, however they differ in terms of real estate wealth concentration (defined as the average real estate value owned by richest households relative to the average). For example, Belgium, France, Germany and Portugal have lower concentration in housing wealth, while Finland, Italy, Ireland, Greece, Netherlands and Spain have a higher level of concentration. Data also shows that that among the countries characterized by high real estate exposure, and in some instance concentration, several also had high government debt levels (see Greece, Italy, Spain).

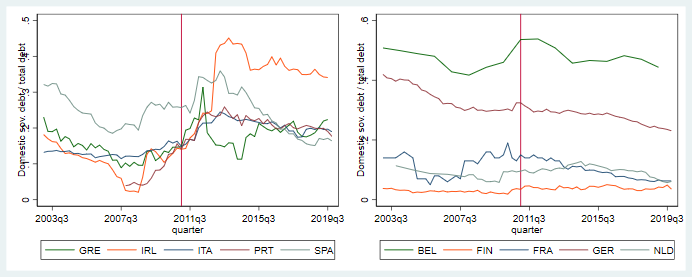

These facts reveal a potential link between real estate concentration and the public debt stock allocation that is particularly relevant for household lending and macroeconomic outcomes. The linkage between debt, lending conditions, and the housing market is even more apparent in specific circumstances. During the European debt crisis starting 2011, the financial sector in southern Europe experienced a drying up of wholesale liquidity, which limited banks’ lending ability. Banks play a key role in financing economic activity and are essential for absorbing sovereign securities, as shown in Figure 1 below. During the European sovereign crisis, domestic banks purchased large quantities of rolled over and newly issued national government debt when international investors reduced financing. In addition, because the interbank lending market dried up, financial institutions ended up significantly constrained. This led to a crowding out effect on the household lending market, raising the cost of borrowing and therefore implying a decrease in housing demand and housing prices.

Figure 1: Domestic sovereign debt in domestic banks (total debt ratio) in Euro Area core and periphery countries

Source: Bruegel database of sovereign bond holdings developed in Merler & Pisani-Ferry, 2012.

Most high debt countries experienced a rise in home bias in domestic banks’ balance sheet holdings of sovereign debt. As highlighted in the literature, these circumstances were also the outcome of governments’ moral suasion efforts: in times when access to foreign liquidity is limited, the government can pressure domestic financial institutions to finance sovereign debt. Moral suasion affects borrowers and lenders differently, which further affects lending and housing demand from borrowers as well saving allocation by savers.

Considering nine European countries over the period that spans the first quarter of 2003 until the fourth quarter of 2019 (including the European sovereign debt crisis of 2011), we provide empirical evidence that for lower levels of sovereign debt, a higher level of real estate wealth concentration is associated with less lending towards households. This result is in line with the 2011 Euro debt crisis outcome and the need of banks to reallocate their portfolio. When the level of sovereign debt is relatively high, lending to households is lower, and there are fewer differences among real estate concentration levels. Figure 2 shows the predicted margins of our panel regression analysis for three levels of domestic sovereign debt holding.

Figure 2: Regression margins

To understand the mechanisms behind the interaction between real estate concentration and domestic sovereign debt holdings of banks with household lending, we extend a general equilibrium model with housing and heterogeneous agents who differ in their saving and investment opportunities.

Moral suasion’s efficiency and equity is related to real estate concentration

The model simulations (see our working paper for more details) show that a moral suasion shock increases sovereign bond demand via banks lowering the cost of debt financing for the government, thus increasing the borrowing cost for households. The aim of such an intervention is to increase the demand for public debt and thereby limit the increases in the risk premium. Overall, private lending drops by 15% for our considered shock and, as borrowers reduce their demand for housing, real estate prices decrease while savers substitute deposit holdings with an increase in their housing stock.

If the share of borrowers is higher in the economy, real estate wealth is more concentrated among a smaller group of savers. Since in this situation savers have more wealth, the aggregate amount of savings through banks’ deposits is higher. Moreover, as we can see in Figure 3, as the deposits stock is initially larger, their reduction in response to the higher public debt demand arising from the shock will be smaller. This dampens the crowding out mechanism. With higher real estate wealth concentration, deposits drop less in reaction to a shock, and so does lending to households, thus allowing borrowers to keep more of their housing stock. In addition, more concentrated real estate wealth correlates with smaller consumption inequality drops and a smaller rise in wealth inequality.

Figure 3: Moral suasion shock under different shares

Note: Comparison of impulse response functions, with different shares of borrowers, for the main variables of interest of the model, given a suasion shock of 2.5pp. The collateral constraint of banks is binding and the regulatory constraint is not binding.

Regulation can increase lending efficiency, but also public borrowing costs

Our analysis also considers the case in which the economy is subject to a permanent and always binding regulatory constraint, one that requires the bank’s assets maintain a constant share of sovereign bonds. This constraint can be seen as a macroprudential policy tool responding to the need of controlling risk build-up whilst regulating the exposure to the sovereign. In this context, a moral suasion shock raising the banks’ sovereign bond holdings must be accompanied by a higher supply of private credit in order to keep bond holdings unchanged. This calls for a rise in deposit demand, which is beneficial for household borrowing conditions, while generating higher debt financing costs for the government. Moral suasion under this type of regulation can help reduce wealth inequality even though it worsens consumption for savers and financial institutions and fails to reduce government debt financing costs. It also leads to temporarily higher consumption inequality with a larger impact for countries with more highly concentrated real estate wealth.

Regulation of the loan-to-value (LTV) ratio is another policy instrument available for controlling borrowing conditions and the level of risk taken by financial institutions, subject to important interactions with other regulations. A moral suasion shock can be more effective in controlling the average government cost of borrowing under a more strict LTV ratio (keeping the level of households indebtedness low and releasing banks resources for government lending) as well as under less strict regulation allowing for smaller share of government debt in bank’s assets (calling for less new issuance of debt to cover for economic losses). At the same time, what grants higher efficiency to government debt allocation and borrowing cost, is more detrimental for private (both borrowers’ and savers’) consumption and financial institutions net worth ending up in a lowered output. Our simulations highlight the regulatory conditions for a higher indebtedness for the government imposing moral suasion. We also find that this risk can be accompanied by higher consumption for households and higher incomes for financial institutions and a temporary lowering of inequality.

Figure 5: The role of regulations and constraints tightness

Note: “MH” stands for the model parameter c LTV ratio: low values of this parameter mean smaller mortgages in relation to collateral. “Phib” stands for the model parameter : low level of this parameter mean smaller ratio of bonds on total assets.

While we abstract from liquidity provision channels other than deposits (as monetary policy and foreign financing), our framework highlights the tradeoffs that the banks face under moral suasion and offers an instrument to evaluate the government’s compromises between possible adverse distributional impacts on households and more favorable public debt financing costs.

Andrea Camilli is a Post-Doctoral Fellow at the Department of Economics, Management and Statistics of University Milano-Bicocca.

Marta Giagheddu is an Assistant Professor of International Economics at the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS).

This post is adapted from their paper, “Public Debt and Crowding-out: The Role of Housing Wealth,” available on SSRN.